| The History of the Old Bridge | |

William Edwards

|

William Edwards was born at a farm named Ty Canol, Groeswen in the parish of Eglwysilan in 1719, but lived most of his life at Bryntail another farm in the same parish. His father Edward Dafydd died when he was a child, with reports stating that he was drowned whilst attempting to ford the RiverTaff. Edward's formal education was limited, and it is said it wasn't until he was in his twenties that he learned to read and write in English, his reading before then confined to Welsh literature. He was described by a contemporary as an ‘obstinate, stubborn and self-willed boy', aspects of his character which would stand him in good stead when embarking upon the building of his bridge at Pontypridd. He was also a deeply religious man and became pastor of the local Methodist chapel at Groeswen in his twenties, a position he held until his death. |

Edwards was a self-taught mason who learned solely through self-study and experience. Although he was not unwilling to learn from others and when some masons came to the area to build a blacksmiths shed he assiduously learned to copy their tools and building techniques. His talent in working with stone meant he was soon recognised as the most expert builder in the area. Indeed his reputation was such that when it was decided a stone bridge was required to span the River Taff he was approached to undertake the contract. This contract signed with the Hundreds of Miskin and Caerphilly, called for the building of a bridge over the River Taff and the maintenance of said bridge for a period of seven years. |

|

The Old Bridge 2006

|

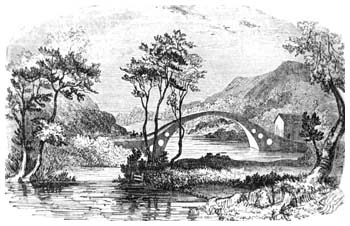

The Bridge TodayThe use of the William Edwards Bridge today is restricted to pedestrians. The structure still stands to this day as a monument to William Edward's ingenuity and perseverance. |

| Building the Bridge | |

|

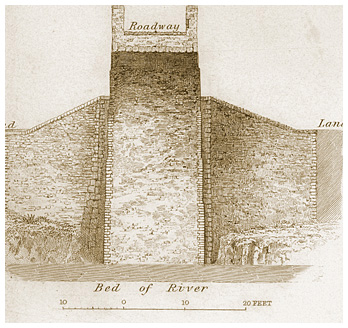

The first of Edward's bridges was more conventional than the single span bridge for which he became famous, consisting of three stone arches. However a little over two years after it was built a heavy storm caused the River Taff to flood. A considerable amount of flotsam was swept into the River becoming trapped against the bridge supports. Eventually the weight and force of this debris caused the bridge to be swept away. This first attempt to build a bridge over the fast flowing Taff and its eventual demise caused Edward's to decide on a more radical solution, that of a single span bridge which would be safe from the dangers of flooding. |

| For an account of the circumstances relating to Edward's attempts to build a single arch bridge over the Taff we are fortunate to have at The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth a number of contemporary manuscripts relating to the events, one known as the Plasybrain manuscript and one written by a contemporary of Edwards known as Thomas Morgan. Thus Thomas Morgan says of Edward's first attempt to build a single span bridge how, ‘…when he had almost finished the arch; the centre timber work gave way and all fell to the bottom.' However the Plasybrain manuscript says how, ‘Just after the first single arch was finished and before the centre was struck, a flood came and carried all away.' Whichever of these accounts is accurate what is clear is that Edward's second attempt to cross the Taff had once again ended in failure. Most men would have been daunted by such successive failures, however Edwards once again attempted to build a single span over the River Taff. |  |

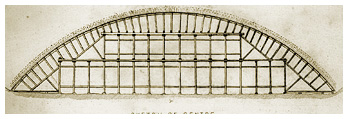

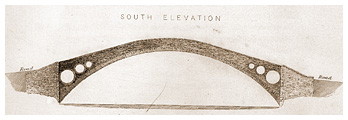

Contemporary reports suggest that this time the bridge was actually finished and stood for a period of about six weeks before collapsing. Edward's inexperience in this type of construction had become apparent with the finished bridge being ill balanced forcing it's keystones out once again causing a collapse. The ‘Gentleman's Magazine' of the time reported how, ‘…the floods have carried away an arch built over the Taff 144 feet wide.' In the article, Theory of Arches and Pontypridd' it is stated that ‘the weight of the bridge was either too great on the haunches or too little on the crown.' It was Edward's fourth and final bridge that was to gain worldwide fame. With this bridge he inserted the famous circular holes, of nine, six and four foot, through the spandrels thereby lessening the weight and pressure on the crown. Edward's bridge was unique and it's fame quickly grew. Despite its fame, ‘The Theory of Arches and Pontypridd', states that as a river crossing Edward's bridge was a dismal failure, ‘being only eleven feet wide between the parapets and so steep that wagons had to use a ‘chain and drag' to descend from the crown. |

|

|

Reports suggest that Edwards attempts to cross the Taff at Pontypridd left him considerably in debt. Malkin at the time stated that he was not indebted to anybody in the construction apart from ‘his own industry and employment.' However his contemporary Thomas Morgan states that by the time of the building of the fourth bridge,' …the mason was considerably in debt and greatly discouraged. But the Lords Talbot and Windsor, who have estates in the neighbourhood pitied his case, and being willing to encourage such an enterprising genius, most generously promoted a subscription among the gentry in those parts.' After his success at Pontypridd both Edwards and his sons continued to build bridges, some of which had long spans and circular voids as at Pontypridd. However with the experience gained from the bridge at Pontypridd Edward's later efforts had built up approaches of reasonable gradient. An indication of the fame and prestige enjoyed by Edwards due in great measure to his achievements at Pontypridd can be shown by his obituary from the Gentleman's Magazine of 1789: |

| ‘At his house near Caerphilly, William Edwards, architect and bridge- builder, or the Rev. William Edwards, for he sustained both characters with equal assiduity and ability… The celebrated bridge on the River Taff called Pont Y Tu Pridd, by the English New Bridge was constructed by this extraordinary man. His fame was diffused through the kingdom and his assistance sought whenever difficulties occurred in constructing bridges. He retained his passion for religious exercises he retained a very large and mingled congregation among which the Methodists predominated, and built bridges to the age of 72 after which he died after sustaining a long illness with exemplary patience.' A bronze tablet at Groeswen Independent Chapel at which William Edwards was the minister for forty years reads, ‘A builder for both worlds… Adeiladydd I'r Ddeufydd' | |