| Aberaman | |

| Before the modern settlement of Aberaman developed with the industrialisation of the Cynon Valley, Aberaman was best known as the seat of the local gentry, the Mathew Family. A branch of a landowning family with interests throughout Glamorgan the family rose to prominence in the Seventeenth century when three members served as High Sheriff of Glamorgan. The family lived at Aberaman Isha, which was later better known as Aberaman House and still exists in a much-modified form today. When the last male heir Edward Mathew died in 1788 Aberaman Estate was divided between his three daughters and their husbands, ending 200 years of influence in the locality. In 1806 the Merthyr Ironmaster Anthony Bacon bought Aberaman House and following his death the property came into the possession of Crawshay Bailey, the owner of Nant-y-Glo and Beaufort Ironworks | |

|

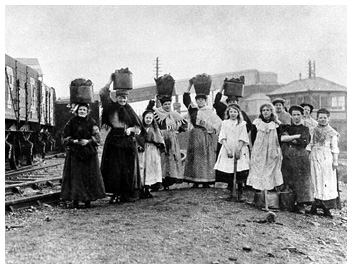

This drawing of Aberaman dated August 16th 1827 by one of the Bacon sisters Emma and Lucy who were the granddaughters of Anthony Bacon the ironmaster, depicts the rural tranquility of the area. They produced many drawings of the Cynon Valley during the period 1820-1830. |

| It is a consequence of Crawshay Bailey's desire to exploit the mineral resources of the Estate that the settlement of Aberaman developed in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. By 1845 Crawshay Bailey had acquired all of the Estate and, after constructing the Aberdare Railway in partnership with J J Guest, he opened the Aberaman Ironworks and associated collieries. Along with Blaengwawr Colliery that David Davis had opened in 1843, these new industrial concerns were the catalyst for the development of Aberaman, to satisfy the need for housing and services that the influx of new workers created. |

Above: Lewis Street c 1890 |

The initial development in the 1840's took the form of a ribbon settlement that spread southwards from Aberdare along Cardiff Road. During the 1850's the settlement began to spread outwards from Cardiff Road as Curre Street, Holford Street, Gwawr Street and Lewis Street, amongst others were constructed. Settlements also tended to grow in the vicinity of the collieries: Incline Row and Bell Place around Aberaman Colliery; Blaengwawr Row and Blaengwawr Cottages to the North at Blaengwawr Colliery. |

|

| Aberaman Hall and Institute | |

|

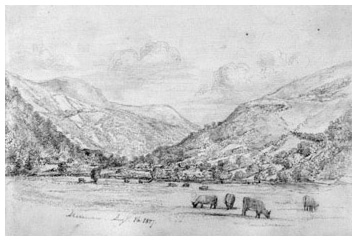

In the later Nineteenth century Aberaman continued to grow southwards until by the time Godreaman was developed in the early years of the Twentieth Century Aberaman and Cwmaman had become joined. By the beginning of the Twentieth Century Lewis Street had evolved into an important commercial centre and when the imposing Aberaman Hall and Institute was opened in 1910 it was clear evidence of the strong civic pride held by the inhabitants of Aberaman. The movement to build a Public Hall and Institute in Aberaman began with a public meeting at Saron Chapel in 1892. However, following a number of setbacks, it was fully fifteen years later on 2nd October 1907 that the ceremony to lay the foundation stone took place. And it was not until 14th June 1909 that the hall was officially opened by Keir Hardie MP. |

The architect of the hall was Thomas Roderick of Aberdare and the builders John Morgan and Son. The hall was built at 171 Cardiff Road, a site previously occupied by the Aberaman Reading Institute, because of its proximity to the commercial centre of Aberaman at Lewis Street. When opened the hall could boast of an impressive list of facilities, including: 2 Billiards Rooms, 2 Games Rooms, Baths and a Swimming Pool in the basement; a Committee Room, Lending Library, Reference Room and Lecture Hall on the Ground Floor; and a main auditorium with seating for 1,800 people plus gallery on the first floor. Those who campaigned to have the hall built hoped it would act as a social and cultural centre for Aberaman. It is obvious from the vast number of activities that took place in the Hall during its history that it satisfied this role. When the Hall was destroyed by fire in November 1994 it left a significant gap in the lives of the people of Aberaman. |

|

| Aberaman Cyclists | |

During the 1880's and 1890's, following the invention of the chain driven safety bicycle, the sport of cycling became extremely popular with people from all walks of life. The sport was as popular in the Cynon Valley as elsewhere, in 1884 the Aberdare Bicycle Club was formed and by 1890 it had developed into a racing club. |

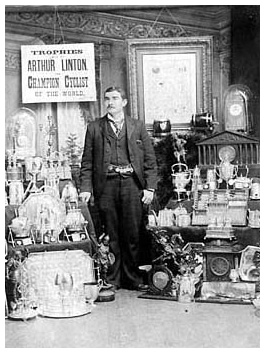

Above: Arthur Linton pictured with just some of the prizes he won during his short but successful career of 3 years as a professional cyclist. |

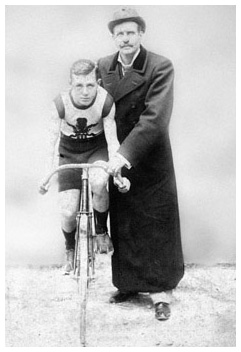

Above: Jimmy Michael with his trainer 'Choppy' Warburton |

1895 was a less successful year for Arthur. He suffered a knee injury and split from his trainer 'Choppy' Warburton. However, it was during the 1896 season that Arthur won his greatest race, the Bordeaux to Paris Race in which he defeated Riviere. Tragically, it seems that this race took too much of a toll on his body and Arthur Linton died of Typhoid Fever in June 1896, only some six weeks after the race. He was just 24 years old when he died. A protégé of Arthur Linton, Jimmy Michael came to public attention in 1894 when he won the Herne Hill race in record time. He too was signed by 'Gladiator' and taken under the wing of 'Choppy' Warburton. In 1895 he continued his run of success, beating the French champion Lesna and later tied with Arthur Linton's record for 50km. At the end of the year he became the World Middle Distance Champion at Cologne. As a result of Jimmy's meteoric rise and the poor year suffered by Arthur Linton, an element of rivalry appeared between Jimmy and the Linton's, especially Tom. |

Shortly after Arthur's death, Jimmy split from 'Choppy' Warburton and then decided to chance his arm in America, where he enjoyed a successful career, breaking many records and amassing a sizeable fortune. Jimmy retired from cycling for a while and instead became a jockey and racing stable owner, though when this venture failed Jimmy returned to cycling in 1902. Unfortunately, he was not the same rider on his return and did not recapture his earlier record breaking form. He died, aged only 29, in November 1904 on the liner 'Savoie' whilst travelling back to New York. The cause of death was an attack of delirium tremens, probably brought on through heavy drinking. |

|

| Aberaman Ironworks | |

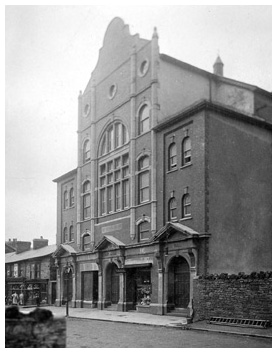

Aberaman Ironworks were the last of the four ironworks in the Cynon Valley to be built. Founded by Crawshay Bailey in 1845 the first iron was puddled at Aberaman Colliery in May 1847. In 1848 the works had one working blast furnace, three engines, a forge, rolling and boring mills, brickworks and limekilns. The works did not, however, prove successful in the long term. By 1854 they were out of blast although they were started again in 1855. A first attempt had been made to sell the works in 1862 for £250,000, but this appears to have been unsuccesful as the works were again put up for sale in 1864 following the retirement of Crawshay Bailey. The works were bought by the Aberaman Iron Company, although this company was wound up in 1867 when the whole concern was bought by the Powell Duffryn Company. The works had stopped in 1866 and were never again put into blast. Click here for a more detailed map |

|

| Aberaman Coal Industry | |

|

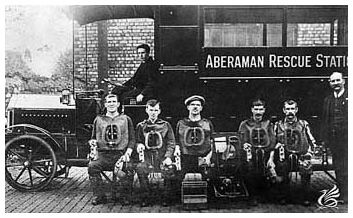

During the second half of the Nineteenth Century, the Aberaman area developed as one of the most important centres of the coal industry in the Cynon Valley. With the development of the Aberaman Ironworks by Crawshay Bailey acting as a catalyst, by 1850 four major collieries had developed in the vicinity. Left: Aberaman Mines Rescue Team c1914 |

Blaengwawr Colliery was opened in 1843 by David Davis. Following his death in 1866 control passed to his sons until the colliery was closed in 1885. The colliery did not reopen until the Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company bought it in 1914. The colliery was closed for good in 1926. Right: Blaengwawr Level c1910 |

|

Treaman Colliery (Nici-Naci) was sunk by David Williams by 1850. By 1866 the colliery had come under the control of Crawshay Bailey so ownership passed to the Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company following his death in 1866. The colliery was closed in 1912. The nickname Nici-Naci came from the noise the rope made travelling over the headgear that could be heard throughout the village. Other collieries and levels sunk later in the area included the Meadow Pit (1864 - c. 1910), Level Fach (1869 - c. 1914) and the Blaengwawr Levels (1903 - 1935) |

|

| The 1910 "Block Strike" | |

By 1910 the Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company was the predominant force in the coal industry of Aberaman. This was an era of growing industrial discontent in the industry as the increasingly radicalised miners came into conflict with the powerful colliery combines over a number of issues. At the end of 1910 events came to a head and two strikes erupted as miners attempted to defend their working rights and customs from the changes being wrought by the combines in a process of 'rationalisation'. |

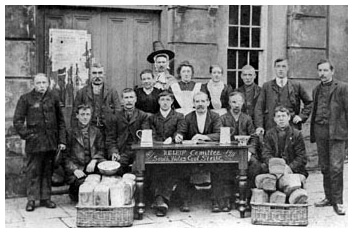

Above: Cwmbach Relief Committee during the 1910 Strike |

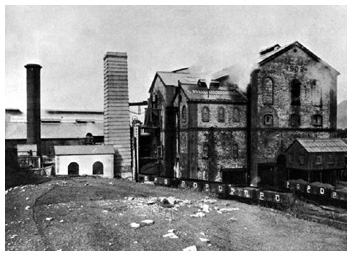

Above: Middle Duffryn Washery and Power Station c1920. Attacked by rioters on 8th November 1910 |

At a mass meeting held at Aberdare on 21st October a list of 18 grievances were drawn up, which put the issue of firewood and the use of machinery to the fore. Another important issue was the payment for abnormal places where a collier may encounter difficult working conditions. |

| The attacks by the crowd were beaten back by 29 police officers who used the extraordinary tactics of electrifying the perimeter fence and spraying hot water from the boilers on to the crowd. When the crowd had been disorientated the police charged, pushing the crowd before them down the railway line and on to the canal bank. Some of the demonstrators were actually forced into the canal by the jostling crowd. In all some 60 demonstrators were injured, including one man who was badly burned by the electric fence. | |

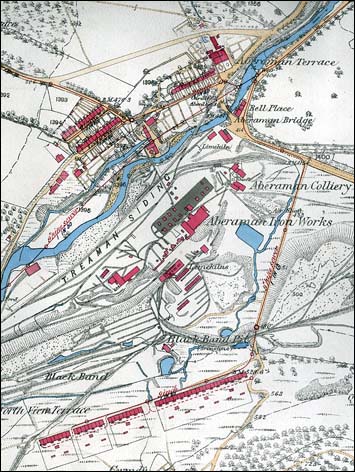

Violence continued to simmer in Aberaman throughout November. Windows of shops were smashed and colliery officials were targeted. One man was surrounded by a crowd of 1,500 on Aberaman Station and assaulted. A chapel service was interrupted by the congregation for a colliery official to be ejected from the building. In one incident a crowd composed mostly of women and children that had congregated outside Aberaman Hall was charged by mounted police. This incident caused a great deal of anger in the area and calls for an enquiry. Ultimately, however, the hardship began to tell on the miners and they were forced back to work on 2nd January 1911. Initially only half of the men employed by Powell Duffryn were given jobs but after repairs had been carried out this number increased. By the end of 1911 some 1,000 miners were still out of work and on lock-out pay, as the Powell Duffryn management took the opportunity to close one colliery and a number of unproductive headings. |

Above: Children and wives of Aberdare Miners taking home coal from the tips during the 1910 "Block" Strike |